Death by Vehicle Blood Testing in North Carolina involves a certain, although limited, amount of discretion by Law Enforcement. There are circumstances where blood sampling may be in addition to standard breath-testing on the EC/IR II.

A combination of breath, blood and urine samples may be obtained in appropriate legal circumstances, even if duplicative in nature and would therefore be subject to administrative licensing consequences for failing to comply.

N.C.G.S. 20-141.1 offenses include:

- Felony Death by Vehicle

- Misdemeanor Death by Vehicle

- Felony Serious Injury by Vehicle

- Aggravated Felony Serious Injury by Vehicle

- Aggravated Felony Death by Vehicle

- Repeat Felony Death by Vehicle Offender

The statutory related offenses are in addition to common law matters; but, double prosecutions for manslaughter under the same factual scenario are specifically excluded under N.C.G.S. 20-141.4(c).

No person who has been placed in jeopardy upon a charge of death by vehicle may be prosecuted for the offense of manslaughter arising out of the same death; and no person who has been placed in jeopardy upon a charge of manslaughter may be prosecuted for death by vehicle arising out of the same death.

Statutory Clarification

Governor Pat McCrory signed into law AN ACT TO CLARIFY WHEN A LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICER IS REQUIRED TO REQUEST A BLOOD SAMPLE WHEN CHARGING THE OFFENSE OF MISDEMEANOR DEATH BY VEHICLE on October 20, 2015.

The Act itself addresses several different issues, one being an amendment to subsection (b5) of N.C.G.S. 20-139.1, which sets forth the procedures for obtaining chemical analysis pursuant to N.C.G.S. 20-16.2.

In North Carolina, a person is deemed to “consent” to testing if charged with an “implied consent offense.”

Implied Consent and Chemical Analysis

N.C.G.S. 20-16.2 reads in relevant part:

Any person who drives a vehicle on a highway or public vehicular area thereby gives consent to a chemical analysis if charged with an implied-consent offense.

The theory and history behind “implied consent offenses” are somewhat more complicated.

In North Carolina “implied consent offenses” are normally associated with offenses involving impaired driving, or an alcohol-related offense, subject to the procedures set forth in North Carolina General Statute 20-16.2 and may include but are not limited to:

- Impaired driving under North Carolina General Statute 20-138.1

- Felony death by vehicle under North Carolina General Statute 20-141.4

- Misdemeanor death by vehicle under North Carolina General Statute 20-141.4

- Second degree murder under North Carolina General Statute 14-17, or involuntary manslaughter under North Carolina General Statute 14-18, when predicated on impaired driving

- Impaired driving in a commercial vehicle under North Carolina General Statute 20-138.2

- Driving by persons less than 21 years old after consuming alcohol or drugs under North Carolina General Statute 20-138.3

- Impaired instruction under North Carolina General Statute 20-12.1

- Driving while license revoked under North Carolina General Statute 20-28

- Transporting an open container of alcoholic beverage after consuming alcohol under North Carolina General Statute 20-138.7

- Felony Serious Injury by Vehicle N.C.G.S. 20-141.4

- Aggravated Felony Serious Injury by Vehicle N.C.G.S. 20-141.4

- Aggravated Felony Death by Vehicle N.C.G.S. 20-141.4

- Repeat Felony Death by Vehicle Offender N.C.G.S. 20-141.4

Freedom of Movement

Why does the State get to say you “consent” to testing? Can you revoke consent? Can you clear up the issue by saying, “I don’t consent?”

The answer involves consideration of the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the United States Constitution which states, “The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.”

The Freedom of Movement has been deemed a fundamental right of citizenship; yet, the method of movement is not necessarily guaranteed nor without restrictions.

While reasonable minds may differ, the prevailing logic on “implied consent” can be boiled down into a single statement:

Driving is a privilege, not a right

The United States Supreme Court has recognized a fundamental right to interstate travel. Attorney General of New York v. Soto-Lopez, 476 U.S. 898, 903, 106 S.Ct. 2317, 90 L.Ed.2d 899 (1986) (Brennan, J., plurality opinion).

Burdens placed on travel generally, such as gasoline taxes, or minor restrictions or inconveniences impacting interstate travel, such as toll roads, do not constitute a violation of that right. Kansas v. United States, 16 F.3d 436, 442 (D.C.Cir.1994).

The United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit in Miller v. Reed opined:

The plaintiff’s argument that the right to operate a motor vehicle is fundamental because of its relation to the fundamental right of interstate travel is utterly frivolous.

- The plaintiff is not being prevented from traveling interstate by public transportation, by common carrier, or in a motor vehicle driven by someone with a license to drive it.

- What is at issue here is not his right to travel interstate, but his right to operate a motor vehicle on the public highways, and we have no hesitation in holding that this is not a fundamental right.

One does not have a fundamental “right to drive.”

In Dixon v. Love, 431 U.S. 105, 112-16, 97 S.Ct. 1723, 52 L.Ed.2d 172 (1977), the United States Supreme Court held that a state could summarily suspend or revoke the license of a motorist who had been repeatedly convicted of traffic offenses with due process satisfied by a full administrative hearing available only after the suspension or revocation had taken place.

Implied Consent in North Carolina

The North Carolina Supreme Court in Sedars v. Powell wrote: “[A]nyone who accepts the privilege of driving upon our highways has already consented to the use of the breathalyzer test and has no constitutional right to consult a lawyer to void that consent.”

One interesting point that one would be remiss in failing to acknowledge is that the North Carolina General Assembly has provided, via statute, the opportunity to “willfully refuse.”

As such, while there does not appear to be a constitutional right pertaining to the right to drive or ability to “not consent,” North Carolina has provided what Shea Denning at the School of Government most wonderfully entitled “a matter of legislative grace.”

Professor Jack B. Weinstein in the 1954 Journal of Criminal Law Criminology & Police Science opined: “[St]ates do not always exercise their police powers to the fullest extent of constitutional limitations and that implied consent statutes codify protections against police abuse.”

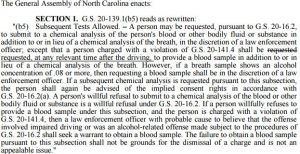

Legislative Modification(s) to Statute

Shall be requested requested, at any relevant time after the driving

The General Assembly of North Carolina enacts: SECTION 1. G.S. 20-139.1(b5) reads as rewritten: “(b5) Subsequent Tests Allowed. – A person may be requested, pursuant to G.S. 20-16.2, to submit to a chemical analysis of the person’s blood or other bodily fluid or substance in addition to or in lieu of a chemical analysis of the breath, in the discretion of a law enforcement officer; except that a person charged with a violation of G.S. 20-141.4 shall be requested requested, at any relevant time after the driving, to provide a blood sample in addition to or in lieu of a chemical analysis of the breath. However, if a breath sample shows an alcohol concentration of .08 or more, then requesting a blood sample shall be in the discretion of a law enforcement officer. If a subsequent chemical analysis is requested pursuant to this subsection, the person shall again be advised of the implied consent rights in accordance with G.S. 20-16.2(a).

Carolina Criminal Defense & DUI Lawyer Updates

Carolina Criminal Defense & DUI Lawyer Updates